Ring around the Rosie

A pocket full of posies

Ashes, ashes

We all fall down.

"Communication is the beginning of understanding"

The first independent Muslim state in Central Asia, that of the Samanids, emerged in the ninth century. Its capital was Bukhara, which under Samanid rule became the showplace of Central Asia, and from its strategic position on the Golden Road became one of the great commercial centers of the Muslim world: Hoards of Samanid coins have been found as far afield as Scandinavia. The court languages were Arabic, Persian and Turkish.

By the 10th century Buddhism, Manicheism and Zoroastrianism had virtually ceased to exist in Central Asia. The majority language had become Turkish, the majority faith Islam. Central Asia had fully entered the cultural orbit of the Middle East, and was no longer as open as it had once been to Chinese and Indian influences. Samarkand and Bukhara became rich and grew into large metropolises.

The murder of 450 Muslim merchants at a place called Otrar in the year 1218 changed the face of Central Asia, and indeed, of the world, for it triggered the most devastating invasion of steppe nomads in history. Among the merchants was an envoy of Genghis Khan, leader of the Mongol hordes. He punished this interference with free trade on the steppes by unleashing 200,000 men, first against Otrar, then against Samarkand. Soon all of Central Asia and Persia had felt the wrath of the Mongols: More than five million people were killed in these two areas alone. The cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, Balkh and Marv were sacked with terrible loss of life.

Genghis Khan's sons conquered China and devastated Iraq. They destroyed Baghdad in 1258, murdering the last Abbasid caliph, and one of them, Kubilai, founded the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in China in 1260.

Oddly, one of the results of the Mongol conquest was closer links between East and West. The Mongols ruled from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, and controlled the Steppe Route to Europe through Russia. For the first time, envoys from Europe as well as merchants were able to travel safely under Mongol protection from Europe to China. Marco Polo is the most famous of the many Europeans who made their way east during the so-called "Mongol peace," which lasted more than a century, and it was at this time that Europe and China first came into direct contact.

It may seem strange that European powers such as the Venetians, the French under Louis IX, and even the Pope should attempt to make contact with the dread Mongols - the self-styled "scourges of God."

But in the Mediterranean basin, this was the time of the Crusades. The small Christian principalities on the Syrian and Palestinian coast were greatly threatened by the Seljuq Turks, who had taken the initiative in the Muslim reconquest of Crusader territories. The Christians thought that by allying themselves with the Mongols they could together put an end to Muslim power in the Levant and Asia Minor.

Indeed, the Venetians had already taken advantage of the Mongol occupation of the northern steppes to set up trading colonies on the shores of the Black Sea, and Venetian intelligence agents had already made contact with the Mongol court in Karakoram.

Genghis Khan was determined that his empire should not prove as ephemeral as some that had preceded it. Before his death in 1227, he began setting up an efficient civil service and a network of post roads with relay stations and - perhaps most important of all - settling the question of succession. That was the rock upon which so many previous dynasties had come to grief, barely outliving their founders. It is interesting that Genghis Khan, who was almost certainly illiterate, hired Chinese advisers - experienced civil servants - to establish and administer his state.

Genghis Khan's sons and grandsons continued his policies in a remarkable example of family solidarity. In 1260 Kubilai, grandson of Genghis, was elected Great Khan of the Mongols and it was to his court that the Polos of Venice made their way.

They had been preceded by a few years by a papal emissary named John of Plano Carpini, who in 1246 made his way to the encampment of one of Ghenghis Khan's grandsons, Kuyuk, with a message from the Pope urging him to be baptized and rally to the Christian cause. Since Kuyuk was a thorough pagan, this message fell on deaf ears, and John of Plano Carpini returned to Europe with a sobering account of Mongol realities. The Vatican Library still retains letters from the Mongol khans in response to these rather naive embassies; they are beautifully written and quite insulting.

John was followed by another Franciscan emissary, named William of Rubruck, whose account of his trip to the court of Great Khan Mongke in 1255 is one of the most informative and lively accounts of Mongol society ever written. But manuscripts of the Itinerarium were not widely circulated in the Middle Ages - only five are at present known - and his account, intelligent and observant as it is, would have sunk into oblivion had Roger Bacon not made an abstract of it in his Opus Maius.

The opposite is true of Marco Polo's famous account of his trip to Khanbalik - today's Beijing - a few years later. Il Milione, as it came to be known, was copied and recopied, and when printing was invented went through numerous editions. It has remained one of the most popular books of travel ever written.

The Polos were a family of Venetian merchants who established themselves first in Constantinople, then in the Venetian trading posts of the Black Sea. Before Marco Polo's birth, his father, Nicolo, and his elder brother Mafeo visited Bukhara, where by great good luck they met Mongol officials who invited them to visit Kubilai Khan. They were apparently the first Europeans Kubilai had ever encountered, and he charged them to deliver a message to the Pope, asking him to send a delegation of Christians to take part in a public debate between various faiths. Unlikely as it may sound, this was a favorite pastime of the Mongol court.

The Polos finally made their way back to Venice after an absence of more than 15 years. Nicolo discovered that his wife had borne him a son shortly after his departure from Venice so many years before; this was Marco, who later accompanied his father and his uncle on their return trip to the Mongol court, begun in 1271.

The Polos sailed to Acre, crossed Syria and Iraq - where they saw the effects of the Mongol sack of Baghdad - and made their way across Central Asia to Balkh. They crossed the Pamir Mountains, passed through Kashgar and Khotan and, after crossing the terrible desert of Lop, reached Dunhuang and the Gansu Corridor. Eventually they made their way to Khanbalik and met Kubilai, apparently entering his service. They stayed in China for some 17 years.

Marco Polo's account of China is the first description of that country in a European language, and the Polos appear to be the first Europeans ever to travel the whole length of the Silk Roads. It was not until the Jesuit missions of the 17th century that more scientific accounts of the country began to appear.

When Marco Polo finally returned to Venice and talked of his travels, he was not believed; he - and his account of China, dictated to a cellmate while in prison years later - were dubbed Il Milione, "The Million Lies." It was not until the careful researches of Sir Henry Yule at the end of the 19th century that it was shown how accurate his descriptions of China were.

The last empire of the steppes was the one founded by Tamerlane, who claimed descent from Genghis Khan. At the head of a vast horde of Turks and Mongols, he took Balkh in the year 1370; within 30 years, he had made himself master of Central Asia, India, Persia and the Middle East. His descendants, the Moghul kings of India, ruled until the 19th century.

The century after Tamerlane's death saw the emergence of powerful centralized states in the Middle East - the Ottoman Turks, political heirs of the Seljuqs, in the west and the Safavid Dynasty in Persia. Central Asia gradually declined in importance, much of it becoming grazing land for Uzbek tribesmen filtering south. The Uzbeks occasionally formed states, but Muslim Central Asia - now beginning to be known as Turkestan, the land of the Turks -never recovered its economic importance.

The Portuguese discovery, in the late 15th century, of the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope to India very quickly led to direct sea trade between Europe and the Far East. Central Asia was no longer the crossroads of the world, and the nomads of the northern steppes, though superb horsemen and warriors as always, were no match for the Ottoman and Safavid armies equipped with the latest firearms. The nomads turned their attention to the vast lands of Russia, and the Middle East and China no longer trembled to their hoof-beats. Samarkand, Bukhara, Ferghana and Tashkent, the once-great cities of the Golden Road, preserved only the romance of their names and the vague memory that once, long ago, they had somehow been important.

Tamerlane (1336 - 1405) - The Last Great Nomad Power

http://www.silk-road.com/artl/timur.shtml

Tamerlane, the name was derived from the Persian Timur-i lang, "Temur the Lame" by Europeans during the 16th century. His Turkic name is Timur, which means 'iron'. In his life time, he has conquered more than anyone else except for Alexander. His armies crossed Eurasia from Delhi to Moscow, from the Tien Shan Mountains of Central Asia to the Taurus Mountains in Anatolia. From 1370 till his death 1405, Temur built a powerful empire and became the last of great nomadic leaders.

Character and Personality.

There are abundant ancient sources written about Tamerlane. We have the primary source from Spanish Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, sent by King Henry III of Castile on a return embassy to Tamerlane. There is also a Persian biography of Tamerlane by Ali Sharaf ad-Din and the Arab biography by Ahmad ibn Arabshah; from Marlowe to Edgar Allan Poe, he continues to fascinate us as hero or viper.

Timur claimed direct descent from Jenghiz Khan through the house of Chagatai. He was born at Kesh (the Green city), about fifty miles south of Sarmarkand in 1336, a son of a lesser chief of the Barlas tribe. Sharaf ad-Din explained that he received arrow wounds in battle while stealing sheep in his twenties and left him lame in the right leg and with a stiff right arm for the rest of his life. But Tamerlane made light of these disabilities; by 1369 he had possessed himself of all the lands which had formed the heritage of Chagatai and, after being proclaimed sovereign at Balkh, made Samarkand his capital.

He was said to be tall strongly built and well proportioned, with a large head and broad forehead. His complexion was pale and ruddy, his beard long and his voice full and resonant. Arabshah describes him approaching seventy, a master politician and military strategist: steadfast in mind and robust in body, brave and fearless, firm as rock. He did not care for jesting or lying; wit and trifling pleased him not; truth, even were it painful, delighted him.....He loved bold and valiant soldiers, by whose aid he opend the locks of terror, tore men to pieces like lions, and overturned mountains. He was fautless in strategy, constant in fortune, firm of purpose and truthful in business.

Acre. oft times called Antioch

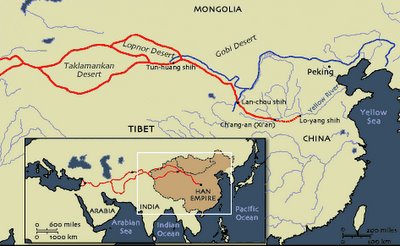

There was never on the Silk Road, but rather a network of routes across mountain, steppe and desert. Starting from the Han capital of Chang-an, near the Yellow River, these routes traversed Asia and the Middle East, ultimately ending in the Levantine ports of Antioch, Acre and modern-day Beirut. From there, the precious cargos of silks, spices and crafts were carried by ship to Rome and Alexandria in the ancient world and ultimately to Venice and Constantinople during the Middle Ages.

click here to see the video: http://www.zippyvideos.com/9538961891681026/15376_1129189286/*podwall

The Black Death

It is most commonly believed that the bubonic plague was originally endemic in populations of infected ground rodents in central Asia, as it was a known cause of death among migrant and established populations in that region. However, it is not entirely clear where the fourteenth-century pandemic started. The most popular theory places the first cases in the steppes of central Asia, though some speculate that it originated around northern India. From there, supposedly, it was carried east and west by traders and Mongol armies along the Silk Road, and was first exposed to Europe at trading ports in Sicily.

Whether or not this theory is accurate, it is clear that several pre-existing conditions such as war, famine, and weather contributed to the severity of the Black Death. A devastating civil war in China between the established Chinese population and the Mongol hordes raged between 1205 and 1353. This war disrupted farming and trading patterns, and led to episodes of widespread famine. A so-called "Little Ice Age" had begun at the end of the thirteenth century. The disastrous weather reached a peak in the first half of the fourteenth century with devastating results worldwide.

In the years 1315 to 1322 a catastrophic famine, known as the Great Famine, struck all of Northern Europe. Food shortages and sky-rocketing prices were a fact of life for as much as a century before the plague. Wheat, oats, hay and consequently livestock were all in short supply; and their scarcity resulted in hunger and malnutrition. The result was a mounting human vulnerability to disease due to weakened immunity. The European economy entered a vicious cycle in which hunger and chronic, low-level debilitating disease reduced the productivity of labourers, and so the grain output suffered, causing the grain prices to increase. The famine was self-perpetuating, devastating places like Flanders and Burgundy as much as the Black Death was to devastate all of Europe.

A typhoid epidemic was to be a predictor of the coming disaster. Many thousands died in populated urban centres, most significantly Ypres. In 1318 a pestilence of unknown origin, sometimes identified as anthrax, hit the animals of Europe. The disease targeted sheep and cattle, further reducing the food supply and income of the peasantry and putting another strain on the economy. The increasingly international nature of the European economies meant that the depression was felt across Europe. Due to pestilence, the failure of England's wool exports led to the destruction of the Flemish weaving industry. Unemployment bred crime and poverty.

Asian outbreak

The central Asian scenario agrees with the first reports of outbreaks in China in the early 1330s. The plague struck the Chinese province of Hubei in 1334. During 1353–54, more widespread disaster occurred. Chinese accounts of this wave of the disease record a spread to eight distinct areas: Hubei, Jiangxi,Shanxi, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Henan and Suiyuan (a historical Chinese province that now forms part of Hebei and Nei Mongul provinces), throughout the Mongol/Chinese empires. Historian William McNeill noted that voluminous Chinese records on disease and social disruption survive from this period, but that no modern scholars, neither in the East nor in the West, have studied these sources in depth.

It appears that movement by the Mongols and merchant caravans inadvertently brought the plague from central Asia to the Middle East and Europe. The plague was reported in the trading cities of Constantinople and Trebizond in 1347. In that same year the Genoese possession of Caffa, a cathedral city and seaport on the Crimean peninsula in modern day Ukraine, came under siege by an army of Crimean Tatar warriors under the command of Janibeg, backed by Venetian forces. Their objective was disruption of a trading empire Genoa had established in Caffa. In 1347, a terrible sickness began to strike the besieging army. According to accounts, so many died that the survivors had little time to bury them and bodies were stacked like cords of firewood against the city walls. Although the Tatar/Venetian alliance broke off the siege, the disease had already spread to the city.

"Ring around the Rosie"refers to a red mark, supposedly the first sign of the plague

"A pocket full of posies" refers to sachets of herbs carried to ward off infection

"Ashes, ashes" either a reference to the cremation of plague victims or to the words said in the funeral Mass..."Ashes to ashes, dust to dust." Sometimes line three is rendered as "Atischoo, atischoo"--sneezing, another sign of infection.

"We all fall down." The Plague was not selective in its victims; both rich and poor, young and old, succumbed.

No comments:

Post a Comment